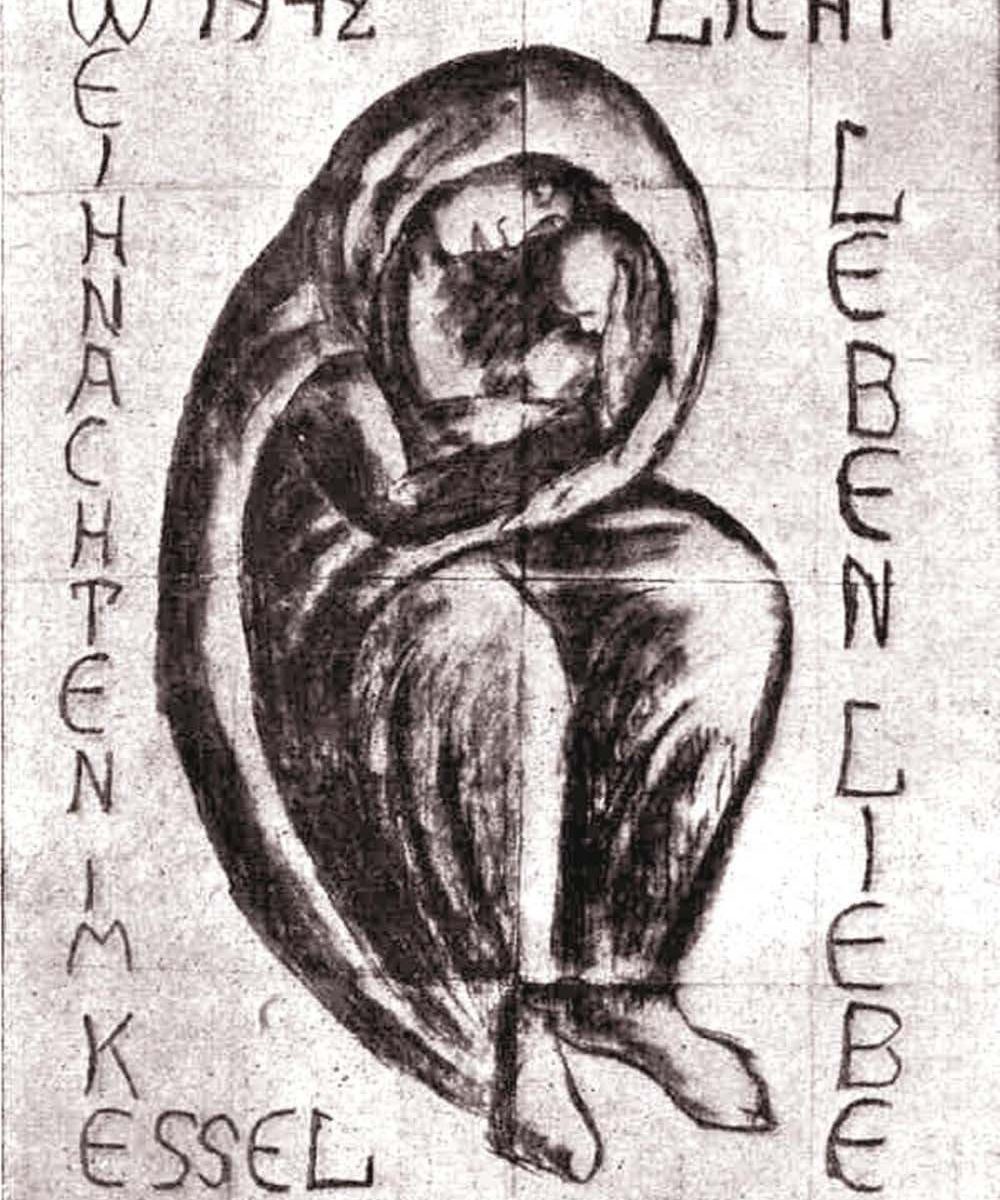

Kurt Reuber’s Stalingrad Madonna – Christmas 1942

By Pastor Bjoern E. Meinhardt

I was visiting Zarephath Lutheran Church in Volgograd (formerly Stalingrad), Russia, in September 2005. As I met with members of the congregation, my eyes were drawn to a work of art on the wall of the fellowship hall.

I had seen the drawing before — in history books and art history books — but I have to admit that I had not paid much attention to it until then, when I saw it in the context of the city in which it had originated.

Kurt Reuber drew “The Stalingrad Madonna” during the Christmas of 1942, as the Battle of Stalingrad raged on. The German inscriptions around the margins of the work read: “Weihnachten im Kessel 1942. Festung Stalingrad. Licht, Leben, Liebe” — Christmas at the Siege 1942. Fortress Stalingrad. Light, Life, Love. The German word Kessel literally means “kettle” or “cauldron.” As a military term it refers to an area that has become encircled during combat and translates as “siege.”

The Battle of Stalingrad was one of the fiercest and bloodiest of World War II. The name Stalingrad evokes the very epitome of sorrow and grief. Christmas is probably the last thing that comes to mind in association with this place.

Christmas and Stalingrad do not seem to go together. And yet, Christmas arrived during the battle, which lasted for 200 days (between July 1942 and February 1943). Even on Christmas, the fighting continued. For the scope of this article, we will not concern ourselves with the details of the battle, which serve merely as the context in which the Stalingrad Madonna was created.

When Ute Tolkmitt-Reuber, the daughter of Kurt Reuber, went to Volgograd in 2005, she visited a museum that featured a replica of General Field Marshall (Generalfeldmarschall) Friedrich Paulus’ command post. She was surprised to see that the exhibit contained photos of her father, a copy of the Madonna, as well as other items pertaining to her father.

She wanted to know why her father was a part of the Paulus-Museum. The director of the museum gave her the following explanation, “General Paulus was the one German responsible for the deaths of a vast number of people on both sides. Kurt Reuber was the other German, who even in the perceived enemy, saw a fellow human being and turned toward their needs.” Though it was forbidden, Reuber provided medical treatment to Russian civilians and prisoners of war.

Who was Kurt Reuber, this “other German”?

He was born on May 26, 1906, in Kassel, a city about 200 kilometers (120 miles) north of Frankfurt. He was a Lutheran pastor, a medical doctor, and an artist. Reuber studied Protestant theology after his high school graduation (Abitur), eventually earning a Ph.D. in the field of theology.

In 1933, the year Adolf Hitler rose to power, Reuber was called as a pastor of the Lutheran church in the small village of Wichmannshausen in the state of Hesse. In his ministry he was outspoken against the Nazis, which led to a series of interrogations by the authorities. Driven by questions on the unity of body and soul, Reuber pursued studies in medicine while serving his congregation. In 1938, he became a Doctor of Medicine.

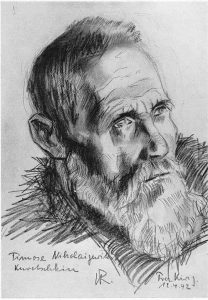

Kurt Reuber was also a very talented artist. After the Stalingrad Madonna, it is Reuber’s portraits of Russian people, drawn during the German campaign against Russia in World War II, that stand out for me. At a time when the reigning Nazi ideology considered Russians (and other peoples) as subhuman enemies, Reuber saw dignity and captured, very aptly, each individual’s character, personality, and humanity.

World War II broke out in 1939. Reuber, despite his criticism of National Socialism, was drafted into the army, not as a military chaplain, but as a field surgeon.

In the summer of 1942, the 6th Army launched its attack against Stalingrad. Reuber joined the troops in November, only a couple of days before the encirclement by the Soviet forces began.

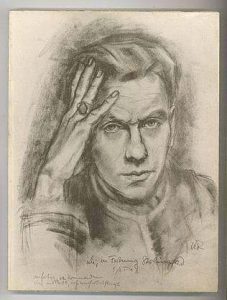

Kurt Reuber, 1942

On February 2, 1943, General Field Marshall Paulus surrendered. This marked the end of the Battle of Stalingrad. Kurt Reuber and some 90,000 soldiers were taken prisoner. After the war only some 6,000 captives survived to return home to Germany. Reuber was not among them. He died, after severe illness, on January 20, 1944, in Yelabuga prison camp (present-day Tatarstan), where he was buried in a single grave.

Albert Schweitzer, the French-German physician and theologian, said the following about his friend Kurt Reuber: “He died as a human being whose goal it was to lose his life in the service to his fellow human beings in order that he might gain it.” (In German: “Er starb als ein Mensch dessen Ziel es war, im Dienst am Menschen sein Leben zu verlieren, um es zu gewinnen.”)

As the circumstances of the German 6th Army in Stalingrad became dire, desperate, and hopeless, Kurt Reuber wanted to create a visual aid to help the soldiers “celebrate” Christmas. He drew the Stalingrad Madonna, with the very primitive materials available to him, as a charcoal sketch on the back of a Russian map.

In the letters that Reuber wrote home to his wife Martha, he described the general mood of the soldiers: They prepared for Christmas “in a soldierlike fashion with stirring love and devotion.” The sounds of “harmonica, fiddle, and singing, and the cheerfulness of the ordinary soldiers (Landser)” temporarily blotted out the sounds of the battle. Food reserves were conjured up and shared with one another. But Reuber also noted that the attacks by the Russians continued throughout their celebration. “How it booms through the Holy Night!” he wrote, describing the artillery barrage that carried on. He fulfilled his duties as a military physician and wrote that his “beautiful festive bunker turned into a field hospital.”

Reuber also referred to his bunker as a “cave of clay.” In the days leading up to Christmas, it “became a studio” for his art work. In a letter to his wife he wrote about his deliberations, “I wondered for a long while what I should paint and in the end I decided on a Madonna with child, or mother and child.”

In order that his wife could visualize the drawing he described it to her in detail: It looked “like this: the mother’s head and the child lean toward each other; and a large cloak enfolds them both. It is intended to symbolize ‘security’ and ‘motherly love.’ I remembered the words of St. John: Light, Life, and Love. What more can I add? In particular if one considers the situation of darkness, death, and hate around us — and the longing for Light, Life, and Love, which is so immeasurably immense within each one of us! … I wanted to signify these three things in this down-to-earth and eternal vision (erdhaft-ewiges Geschehen) of a mother with her child and the security that they represent.”

Reuber went on to describe to his wife how “my Madonna” was received when Christmas Eve arrived and he opened the “Christmas Door” of the dug-out: “My comrades stood spellbound and reverent, silent before the picture that hung on the clay wall. … Our celebration in the shelter was dominated by this picture, and it was with full hearts that my comrades read the words: Light, Life, and Love. … Whether it was a commanding officer or an ordinary soldier, the Madonna was always the source of their inward and outward reflection.”

It is understandable that the notions of security and motherly love, the way they are depicted in the drawing, stirred these very human emotions. We can only imagine what the first viewers of that drawing must have felt in those moments. Perhaps the soldiers imagined what it would be like to celebrate Christmas at home, in the arms of their wives and loved ones, by the Christmas tree. Or perhaps they longed to finally see the child, that was born after they were deployed, safe in the arms of the wife. Maybe they were remembering their own childhoods, the safety and security of their mother’s embrace.

Kurt Reuber’s Stalingrad Madonna is one of the most powerful “sermons” on hope and redemption, love and reconciliation. There are times when a visual work can communicate more clearly and effectively than the spoken word. There are times when a minimalist message, reduced to its most essential words, carries the most power. It is a message that still speaks to us and moves us today: Light, Life, Love.

In January of 1943, the drawing of the Madonna, along with a self-portrait of Kurt Reuber, were flown out of Stalingrad by one of the last supply planes and eventually delivered to his family in Wichmannshausen.

Since 1983, the original Stalingrad Madonna has been on permanent display in the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church (Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtniskirche) in downtown Berlin, Germany, where it is viewed daily by approximately 3,500 people.

An exact replica of the Stalingrad Madonna was gifted to the Cathedral Church of St. Michael in Coventry, England, in 1990, and another to the Kazan Orthodox Cathedral in Volgograd in 1995.

Berlin, Coventry and Volgograd are three cities that suffered unimaginable losses during World War II. Now, these three cities are connected with each other through Kurt Reuber’s Stalingrad Madonna.

The words “Light, Life, Love” send a hope-filled message of reconciliation that needs to be heard everywhere.

For more information, recommended literature (unfortunately available only in German) includes: Martin Kruse (editor), Die Stalingrad-Madonna. Das Werk Kurt Reubers als Dokument der Menschlichkeit, Lutherisches Verlagshaus, Hannover, Second edition, 2012. The photos are from the Kruse book, pages 27 (Madonna), 43 (selfportrait), and 50 (Kurochkin).

Pastor Bjoern E. Meinhardt serves St. Peter’s Evangelical Lutheran Church, a bilingual (English and German) congregation in Winnipeg, Manitoba. You may contact him by email at [email protected].